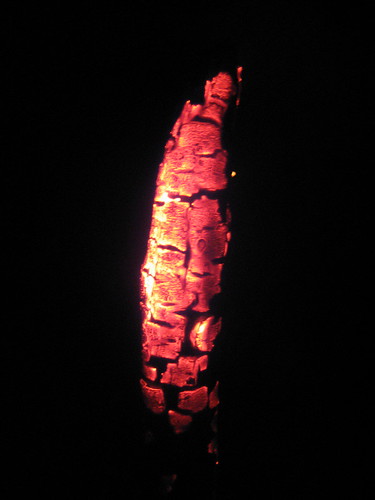

As a kid I could sit transfixed for hours by the firepit Dad built into the hill by our back deck. After I ate my fill of marshmallows, I took the long, thin stick (I’d describe it as a “twig” if it wasn’t four feet long) and put its tip right into the hottest part of the fire. Usually the first round was just a mass of marshmallow goo melting away, but after that, I’d let the tiniest spot on the end of the stick catch fire, pull it to my mouth, blow it out, and then watch that ember glow down to nothing. The dead ember then became my pen. I’d scratch lines in the rocks beside me until I was out of charcoal and then go back to the flame again.

This may be my first lesson in having a writing practice. It certainly was a practice in simple joy.

I don’t write of joy very often. I’m not sure why. I’m not really miserable; it just seems that joy doesn’t come to my language that often. It’s more of something that sits comfortably in the middle of my torso waiting to be seen.

A few years back at the AWP conference, I heard a panel about writing about happiness. All the writers there talked about how hard it was to write about joy or pleasure. They didn’t really come to consensus about why that was, but I took comfort that it was a fairly universal challenge for most of us.

It’s hard to capture joy in words – it’s fleeting and pure and when it comes, we usually embody it rather than analyze it. Maybe that’s for the best; if we took too much time to consider it, would it disappear like the burning ember?

But joy is what I felt on those cool, mountain summer evenings when the fire warmed my face and my breath fed the coals. The simple, mindless joy of watching fire burn and turning it into words.